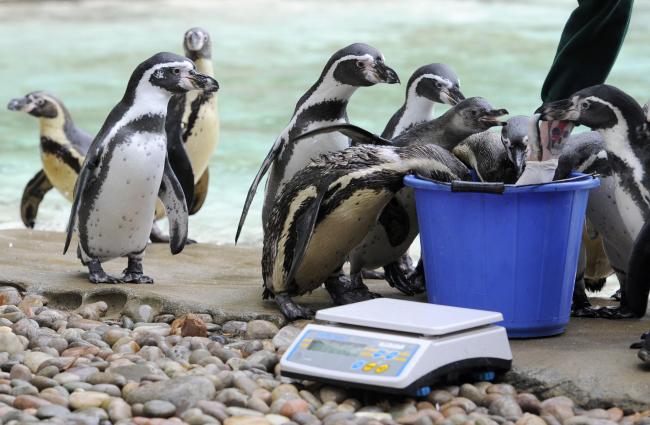

London

- Whales have a special day, pangolins too, and every December all

things simian are celebrated, so it seems only right that penguins

should be similarly lauded with World Penguin Day on Monday. The global

observance was launched four years ago when scientists at a US Antarctic

research centre noticed that, without fail, Adelie penguins returned

from the sea to breed on this day every year. It is now used as a means

of promoting their conservation.

My admiration for these aquatic,

flightless birds rose exponentially during an eight-day cruise around

West Antarctica. Like the other 185 passengers on board the Ocean

Endeavour, departing from Argentina's Tierra del Fuego, I wanted to be

wowed by breaching whales, leopard seals' bloodlust, and nature's

borderless paragliders, albatrosses.

Yet penguins are the fabric

of all wildlife-watching voyages to Antarctica. Always waddling around,

they are ready to entertain when whales can't be bothered to surface,

and are all too often an oily lunch for predators in a sub-zero world

that is as chillingly visceral as it is beautiful.

Even in a

landscape as remote as Antarctica, penguins are facing unprecedented

impact from humans, something I'd learn throughout our 1 500

nautical-mile voyage from Dr Tom Hart of Oxford University. This

hitchhiking penguinologist uses Ocean Endeavour to monitor time-lapse

cameras for his Penguin Lifelines project, whose goal is to better

understand the threat to penguins and their fluctuating populations.

The

first thing to admire about these comical creatures is a tenacity to

exist around the Southern Ocean's frozen, wave-battered shorelines. The

region's rigours were introduced to me by a hefty sea swell as we sailed

south from Cape Horn at the tip of South America during a two-day

crossing down the Drake Passage to Antarctica. I lurched around our

reinforced ship like a drunken sailor, lolling between my comfortable

seventh-deck en-suite cabin, lectures on everything from glaciology to

ornithology, the gym, and Polaris Restaurant for Austrian chef Mannfed's

excellent cordon bleu cooking.

Most of the world's 17 penguin

species exist in the circumpolar Antarctic Convergence Zone, where sea

temperatures range from 6ºC to 2ºC and warm sub-Antarctic and cold

Antarctic currents meet, spawning rich, penguin-favoured feeding grounds

of krill (tiny crustaceans). “Penguins don't like cold water, but

they're not stupid. They like the food these waters bring,” lectured

French ornithologist, Fabrice Genevois.

Halfway down the Drake

Passage, it wasn't long before we spotted our first penguins prospecting

for krill, skimming through the water like Wallis' bouncing bombs

trailed by a black-browed albatross.

Soon after, the Antarctic

Peninsula's ice-entombed isthmus was signposted by a floating behemoth

of an iceberg (imagine the White Cliffs of Dover on a world cruise).

Land duly appeared as Ocean Endeavour nosed between Brabant and Envers

Islands near Neko Harbour on the 65th parallel where, on cue, a pod of

humpback whales was gorging on krill.

The combination of blue-hued glaciers and dusky evening light was bewitching.

Planned

daily trips onto land further increased my admiration for penguins.

Even the pong of their fishy guano didn't deter our fleet of Zodiacs

about to storm Neko Harbour, armed with 400mm lenses primed to pap any

penguin that moved. Were the birds bothered? Not a bit.

On snowy

slopes, against the backdrop of a glacier crevassed into teetering ice

towers and wracked by rumbling avalanches, the Gentoo penguins were

presumably preoccupied with survival. These knee-high birds, with a

distinctive white eye-patch, are one of six Antarctic species that breed

on Antarctic land. It was February, nearing summer's end and time was

ticking for the colony's chicks to mature enough to face the onset of

winter. Both parents made food runs while their downy greyish chicks

fussed to be fed. “I've tried the regurgitated krill, it's quite tasty -

a little salty perhaps,” said Genevois. I hoped chef Mannfred didn't

agree. Elsewhere, mature penguins were preening their moulting feathers.

“These

penguins are losers,” commented the ever-phlegmatic Genevois. “They

have time to moult because they didn't breed or lose their chicks.

Dr

Hart, meanwhile, checked a few of his land-and ice-based cameras, in

place to observe the colonies in situ. He explained that his research

suggested this 2 000-pair colony remains stable and reveals that Gentoo

are remaining around the nesting beaches longer into winter than

previously thought. “But this is a late crèche of chicks and quite a few

won't survive the coming winter,” he cautioned.

Next day it was

Chinstraps' turn to get papped. We sailed down the magnificent Lemaire

Channel, whose mountainous flanks of snow and black basalt were

patterned like a Friesian cow's hide.

Chinstrap penguins are a

little smaller than Gentoo, with porcelain-white faces framed by a

delicate black line around their neck. They live beside the Gentoo on a

snowbound promontory, Port Charcot, named by early 20th-century French

expeditionary, Jean-Baptiste Charcot.

Instead of landing, I took a

kayak out for a penguin-eye perspective of their refrigerated world: an

abstract gazpacho of fractured sea ice and bobbing blue-veined bergs,

everevolving into shapes and textures such as scalloped shells, cubes,

Art Deco curves, and floating toadstools, all inextricably dissolving

into seawater as clear as glass.

Chinstraps barrelled past our

kayaks, surfacing frequently for air. As winter's ice locks the

landscape shut, they will head out to sea, fishing exclusively on krill.

They can load up on 800 grams of krill - one-seventh of their body

weight - to carry back to their chicks.

My admiration for their

environment extended to new levels of respect that afternoon. On the

ship's daily menu is a Wandering Albatross and Polar Plunge. The former

is a gin and Cointreau cocktail; the latter a rites-of-passage dip in

the ocean. Joining some of my fellow passengers queuing to take this

unnecessary excursion, I felt like a mutineer about to walk the plank

into the 1.6ºC brine - initial breathlessness, ice-cream headache, then

shock followed in quick succession. The experience lasted barely a

minute and ended with a Ukrainian waiter proffering a welcome shot of

vodka.

Those same hostile waters host fearsome predators where our

admirably brave penguins risk life and flipper every time they fish.

“If this is a leopard seal I want to see him shredding penguins,” said

Gordon, a no-nonsense pipefitter from Medicine Hat, Calgary. Of course,

nobody wanted to see the little chaps getting eaten, but secretly we

hoped they might lure some of Antarctica's mammalian and winged

predators towards our boat, keen to pick up a penguin.

Orcas, for

whom penguins are surely an hors d'oeuvre, offered only distant

sightings. Yet Gordon's lust for penguin gore was sated by magnificent

leopard seals, so named for their spots. One of these big seals

volleyballed an unlucky Gentoo into the air before devouring it.

“Their skin is quite tough, so the leopards have a job biting through,” explained Genevois.

Jostling

for dessert, Antarctica's mightiest winged scavengers, giant southern

petrels, arrived with powerful vulturine beaks to rip into the remaining

carcass, while petite Wilson's storm petrels, nicknamed Jesus Christ

birds because they seemingly walk on water, snaffled morsels of flying

gristle and blubber. Meanwhile, back at the penguin rookeries, predatory

skuas loitered around the chicks to pick off the weakest.

In spite of the natural violence that surrounds them, penguins' biggest adversary is mankind.

Returning

northwards towards Tierra del Fuego after three days on the Antarctic

Peninsula, Ocean Endeavour called at the scenic South Shetland Isles. We

steamed into Deception Island's flooded caldera: its last eruption in

1971 artistically streaked the snowy slopes with cindery, haematite-red

ash. Nearby is Antarctica's largest Chinstrap colony at Baily Head,

where black volcanic beaches are strewn with 50 000 pairs of Chinstraps.

“It's a big colony,” said Dr Hart, “but numbers have fallen by 39

percent since 1986.”

Our onboard lectures muddied any

oversimplified notions I had about anthropogenically induced climate

change. Certainly, dissolving ice sheets are devastating for penguins.

The recently reported Rome-sized Iceberg B09B grounded onto a beach in

Eastern Antarctica and during four years has decimated an Adelie penguin

colony that now has to detour 60 kilometres in search of krill.

But

such ice break-ups may not be down to humans necessarily, cautioned

onboard glaciologist Dr Colin Souness. He explained that the enormous

Larsen Ice Sheet interlocking the Antarctic Peninsula has badly

fragmented over recent decades, yet Eastern Antarctica has been observed

to cool, hinting at the possibility of natural cycles of climate

change.

However, Dr Hart does see direct human activity affecting

penguins. “I'd summarise climate change, fisheries, disease and

pollution, as penguins' biggest threat,” he outlined. “As an educated

guess I'd say the relationship between climate change and krill-fishing

presents the greatest challenge. When krill is over-exploited by

fishing, he explained, it impacts penguins' ability to gather sufficient

food to raise their young. If the ice sheets melt away, fishing can

potentially penetrate deeper into Antarctica. Among other uses, he

explained how krill is used in food colouring for products such as

farmed salmon and Omega 3 oils.

A final disembarkation in the

South Shetlands allowed us the chance to celebrate penguins one last

time. Aitcho Island is fortified by Giant's Causeway-like columnar

basalt, while humpback whales and leopard seals patrol a broad bay of

black sands embedded by beached icebergs offshore.

Mixed colonies

of Gentoo and Chinstraps played the crowd. Tubby, downy chicks huddled

together, generating a fearful din. Others chased downtrodden parents

who plunged into the sea to escape their persistent offspring. I watched

with admiration a brave Gentoo repeatedly chasing away a menacing skua.

Life

for penguins at the bottom of the world is a lot harder than I'd

imagined. These brave little birds deserve celebrating today. I'll

certainly be raising a glass. Something chilled, of course.

source