Penguin

Posted on Wednesday, June 8th, 2011

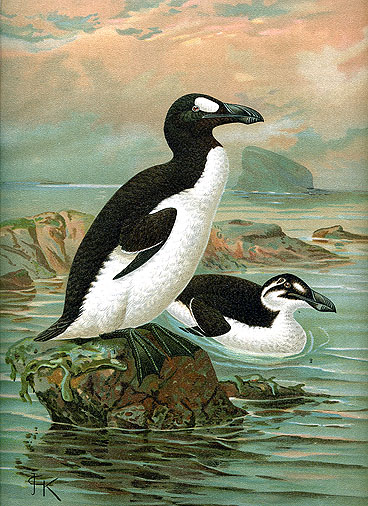

By Anatoly Liberman The extinct Great Auk by John Gerrard Keulemans - Natural History Museum, London

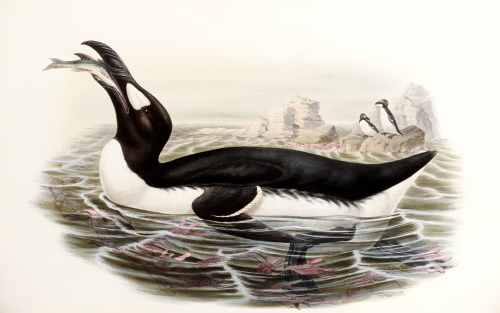

Practically everything that can be said about the origin of penguin has been said in the OED, and in what follows I will only touch on three later works on the subject. It must be admitted that these works are almost as flightless as the bird they discuss. Here is the relevant part of the digest of the OED’s long note, as it appears in The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology: “…of unknown origin; first recorded in both applications [that is, as “great auk” and as “penguin”] in reports published by Hakluyt (1589, 1600); the earliest accounts mention an island of the name; the superficial resemblance to W[elsh] pen gwyn white head, referred to 1582, has suggested that the name was first applied by Breton fishermen to the northern bird. F[rench] pingouin (1600) is still applied to the great auk, the penguin being manchot.” Let us bear in mind that the great auk has a white patch or spot in front of the eye (nothing else is white), whereas the penguin’s head is black.

The main questions being asked about the history of the word are two: whence the confusion between the great auk and the penguin and why “white”? In 1598 the derivation of penguin from Latin pinguis “fat” was proposed, but this is folk etymology, and no one today seems to take it seriously (yet I saw references to it as late as 1938), though it led to the coining of Flemish vetgans and German Fettgans “penguin,” literally “fat goose.” (Magellan also called those birds geese.) The same holds for the word’s fanciful derivation from Engl. pin-wing. Ernest Weekley did not object to the Welsh etymology: “A bolder flight of imagination connects it [the name] with the mythical discovery of America by Madoc ap Owen in the 12th century…. The fact that the penguin has a black head is no serious objection, as bird-names are of very uncertain application (cf. albatross, grouse, pelican, bustard). F[rench] pingouin, earlier (1600) penguin, if not from E[nglish], may be Breton pen gouin, white head.” We will leave Prince Madoc (or Madog) and the Welsh Indians in their folklore obscurity (among others, Skeat summarized the story) and turn to linguists. But I would like to register my amazement at Weekley’s easy dismissal of all ties between the color of the bird and its seemingly incongruous name. Other than that, he is quite right: bird names are often odd and pose many insoluble problems.

William B. Lockwood, the greatest expert in the area of English and Scandinavian linguistic ornithology, wrote:

“Although the inhabitants of islands off the north of Scotland were familiar with the flightless auk, seamen venturing to the New World can have had no clear notion of such a bird. Consequently, when they came upon it in Newfoundland they used a new name penguin. A few decades later, these same men were sailing through the Straight of Magellan where they discovered other flightless birds and promptly named them penguins, too. This we find the only consistent interpretation of the literary evidence as set out in the OED and which also corresponds to the general historical picture.”

However attractive Lockwood’s conjecture may be, the sought-for etymon has never been found. He himself said at the end of his 1969 article: “Further investigation here should be a task for an American linguist.” Some work along these lines has been done, but with no results. I am quoting from a 1997 publication by Victor Golla: “If the word is from an American Indian language, then, the most likely candidates are Beothuk, Inuit, Montagnais, and Micmac. Unfortunately, the accessible documentation of these languages reveals no likely original for penguin. It is especially frustrating that the surviving attestation of Beothuk—the language of the aboriginal people of the Funk Island area—consists of four short late-18th and early-19th century vocabularies… in none of which a name for the great auk occurs.” Funk Island (allegedly called this because of the odor of nitrate and sulphate from the vast amounts of guano and fresh bird droppings found at the roosting and nesting sites there) is the older name of Penguin Island.

Finally, William Sayers, who surveyed the historical sources but made no mention of Lockwood’s objection to the Celtic form, proposed that Breton penn gwynn had been the name applied not to the bird’s white head (which, as we know, is not white, whether auks or penguins are meant) but to the white headland:

“Centuries of bird droppings have left this exposed pale-colored rock coated white…. We can easily imagine interaction, not least linguistic, among the numerous ships’ crews from the fact that in the year 1578 alone 350 Spanish and French vessels and fifty English were fishing in these waters. As the passage along the Newfoundland coast became more familiar, the reference of penn gwynn in the several languages of North Atlantic seafarers with at best a nodding acquaintance with Breton or Welsh became the island’s principal resource—birds—displacing the identification of a topographical feature…. Penguin… is seen to have a specific geographical origin, but… the referent is replaced—headland and landmark giving way to the island’s chief resource, the great auk, colonies of which were also met at other sites. With the extinction of the great auk, the use of penguin in English came to be restricted to comparable birds of the southern hemisphere, the third stage, if we will, in the evolving signification of penn gwynn.”

Source

No comments:

Post a Comment